As Fidel Castro and his Cuban revolution fade, is Cuba rising?

Seismic changes in the communist economy built by Fidel Castro are enriching some Cubans, scaring others, and sparking imaginations: Will the Caribbean gem shine again?

By Sara Miller Llana, Christian Science Monitor Staff Writer

November 27, 2010

MEXICO CITY and HAVANA

This article is part of the cover story project in the Nov. 29, 2010 issue of The Christian Science Monitor weekly magazine.

Antonio Santana and Marina Suarez are children of Fidel Castro's revolution – born into the communism that swept across this island of mambo and mob ties in 1959.

Now thin and graying, with government-issue glasses, Mr. Santana – a pseudonym he asked the Monitor to use out of concern he should not talk to foreign journalists – has had a long career as a state barber. Snipping no-nonsense cuts in a society that overthrew the glamour and glitz of the corrupt Batista dictatorship for social egalitarianism, he and his wife were able to raise twins, a boy and a girl now grown, on his paltry $12-a month salary.

Ms. Suarez, who manages a tidy, crisp look in Cuba's tropical heat, had a career as a government secretary and raised two sons – now 15 and 24 – on her own. Though her $14-a-month salary was pitifully small, she valued the job security.

Like all of their contemporaries who have been housed, fed, and employed by the state, Santana and Suarez grew up as pawns in Mr. Castro's trial of free health care and education, state-owned industry, and collectivized agriculture.

As waves of their fellow countrymen fled, and as Castro raged against the sea of capitalism that isolates this island – even providing the stage for cold-war nuclear brinkmanship – the lives of people like Santana and Suarez have been calm if grindingly poor. Never forced to fret over college funds and health-care copays or contend with gaping divides between rich and poor, they've never faced the dramas of market-driven economies. Like most Cubans, they've earned little in their lives – because they have needed little.

But now these children of the revolution have awoken to the hint of a new revolution: In the waning days of Castro's power, a decided tilt toward a market economy has shifted the paternalistic burden from the struggling government onto individual citizens.

Ever since the 1991 fall of the Soviet Union and the decline of support from Cuba's communist brethren, steady tinkering with the economy has given way to the biggest economic upheaval the island has faced since the revolution – the layoff of half a million workers and a push toward private entrepreneurial activity.

The bottom line for Suarez, for example, was a pink slip and a sense of betrayal: "I never thought Cuba could do this, because the government always protected us."

But for Santana, being kicked off the government payroll has been dazzling. Told to start his own business, he has to pay rent; and if his scissors dull or clippers break, he shoulders the expense. But he's also pocketing the pesos he earns – the equivalent of $40 a month, more than three times his previous income.

"I am not a millionaire, but I am better off than others," says Santana. "[I have] the liberty to have my own schedule, prices, and services. I am the boss of myself. Everything that happens is my responsibility, and that is a good feeling."

Click here to keep reading.

Monday, November 29, 2010

Thursday, November 25, 2010

Lechon Asado y Flan de Leche a la Cubana!

While El Yuma has expended a lot of kilobytes debating the finer points of the Cuban blogosphere and Cuba's economic reforms, two post that remain perennial favorites (both ranking in the top five of my most visited posts) are about something that we all can agree on (well, except for observant Jews and Muslims - who both agree that "el puerco es un asco!"):

So, as a way to wish all my readers a Japy San Guivi, I am linking you back to those two posts from a year ago. If you make either of these dishes and live within an hour of NYC, you have to invite me over to share the wealth! I'll bring the cafe y ron!

Abrazos a todos!

Saturday, November 20, 2010

La Joven Cuba Responds

El Yuma just received the following interesting and inviting comment from Harold, one of the administrators at La Joven Cuba:

Harold said...

The blog La Joven Cuba was an idea of a few young people at the Matanzas University. As an administrator, I can tell you that we try to approach Cuban topics in 2 areas:

-Defend our political system (without giving up our critical point of view).

-Debate our internal troubles and limitations. To criticize all that it needs to be changed.

Our visitors are mostly foreign, that makes the controversy very difficult for us, anyhow... we don't give up talking about hot, difficult topics.

We expect you there...The site also recently added a section called "Cartas a LJC," where they make space for "Letters to the Editor," allowing for "the promotion of a respectful exchange of ideas so that people with other ideological positions can express their opinions." If you want to send them a letter or extended comment, use this e-mail address: colaboradores.lajovencuba@gmail.com.

Here's their original Spanish statement:

"Nuestra intención es propiciar un intercambio respetuoso en el que personas de otras posiciones ideológicas tengan también derecho a expresar sus opiniones."Let the debate begin...

Keep reading to learn a bit more about the man and movement who inspired the name La Joven Cuba, Antonio Guiteras Holmes (1906-1935) [an outtake from my book on Cuba].

Thursday, November 18, 2010

Estoy enamorado...

El Yuma has fallen in love with La Yuma.

Not the country but the title character of this new Nicaraguan film (played by Alma Blanco pictured above).

Click here to see the trailer on You Tube!

Not the country but the title character of this new Nicaraguan film (played by Alma Blanco pictured above).

Click here to see the trailer on You Tube!

La Yuma Boxes Her Way From Managua To Miami

Starting Sunday November 21

For info on the film and showtimes go to the Coral Gables Art Cinema site.

La Yuma paints a portrait of the heroine's violent family and community, along with her "band-of-outsider" friends, while at the same time following her affair with a university student who is from "the other side of the tracks." Unusual in its intensity and authenticity, La Yuma is Nicaragua's submission for this year's Academy Awards. Although it has played at many international festivals, broken box office records in Managua, and opened theatrically in Europe, this is its first regular theatrical release in all of North America.

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

Back in Business...?

A worker prepares tables at La Guarida,

Havana's best known paladar, or private restaurant.

By Javier Galeano, AP Photo (USA Today)

Thanx to the blogger/journalists Tracey Eaton and Ernesto Hernandez Busto I have been informed that two of Havana's leading paladares, El Huron Azul and La Guarida, have both recently reopened and are back in business.

I wrote about them both previously in my series of posts "Requiem for La Guarida" (see also here, here, and here). However, Eaton traveled to Cuba this summer, dined twice at Huron Azul and posted this comment on my blog. He also wrote this brief post about HA on his own blog Along the Malecon.

Hernandez Busto also linked to the following article on his blog earlier today. For those who don't read Spanish, the article describes the reopening of La Guarida - the culinary destination of the international "jet set" and the place where the breakout Cuban film Strawberry and Chocolate was filmed.

The article features an interview with Enrique Núñez (whom I also interviewed years ago) and points out that some of his main obstacles have now been removed given the new self-employment legislation that took effect a few weeks ago.

Among the changes that will benefit his business are (1) the ability to sell dishes that feature shrimp, lobster, and beef, (2) the expansion from a maximum of 12 to 20 chairs in any "paladar," (3) and the allowance of legal employees. (Previously, the law stipulated that paladares could/must employ only two workers and that they had to be members of the "household" - now, however, there is no limit on the number of employees and they need not live on the premies!)

Reabre la "paladar" cubana del jet set donde se rodó "Fresa y Chocolate"

17 de noviembre de 2010

Enclavada en un derruido edificio de un popular barrio de La Habana, "La Guarida", la famosa "paladar" cubana donde se rodó "Fresa y Chocolate", reabrió sus puertas para placer de sus comensales, entre quienes, en 15 años, se cuentan reyes, estrellas de Hollywood y "top models".

Soy Paquito - El de Cuba... y Soy Yasmin - La de Cuba...

I just discovered two fascinating new Cuban blogs. The first is called, Paquito, el de Cuba, and is written by the proud Cuban journalist, communist, gay, sero-positive, father, Francisco Rodriguez.

Read below for my translation of his provocative profile. I discovered Paquito while reading a recent article at IPS/Havana Times by Patricia Grogg, "Home Internet, Distant Dream in Cuba," which quotes him as saying:

“Any measure to improve connectivity and expand Cuba’s capacity to access the internet is positive, because it will allow more voices on the island, both institutional and individual, to be heard worldwide.”

Grogg also quotes him as saying:

“Greater (internet) access for civil society, including institutions and individuals, would contribute to demonstrating that the (Cuban) revolution isn’t as bad as some people make it out to be, nor as perfect as others would like to think. To do this, we need technology, but also training in diversity of thought and viewpoints.”

On the other hand, Grogg also cites another blogger, the Marxist, feminist blogger Yasmín Portales (a woman with a sharp tongue and a sharper mind, originally affiliated with Bloggers Cuba, whom I recently met at LASA in Toronto) who told Grogg that she did not believe that the newly announced [fiber optic] cable [from Venezuela] would increase residential connections, “because that’s not where the state’s interest lies.”

Readers are encouraged to check out Yasmín's blog. There she describes herself this way:

"Soy cubana. Mi vida es un fino equilibrio entre el ejercicio de la maternidad, el feminismo y el marxismo crítico."

These clearly are not your mother's (or grandmother's) communists or marxists!

Tuesday, November 16, 2010

Revista Voces vs. La Joven Cuba

Let a thousand bloggers bloom! Competition + Diversity (x Freedom) = Qualtiy!

A year ago when I launched El Yuma I quickly became acquainted with the emerging Cuban blogosphere.

However, between December 2009 and January 2010, Bloggers Cuba disappeared from the web inexplicably (I have heard rumors but have no facts). Some of their leading bloggers, such as Elaine Diaz at La Polemica Digital and Yasmin Portales at En 2310 y 8225 continue to blog at their own sites but the group portal as such no longer exists. The group still survives today in a PDF e-zine that has come out sporadically over the past year (see here, here, here, and here for examples).

Now there seems to be a new kid on the "blog": La Joven Cuba.

I'm still unclear on the whole story behind this new blog portal (the site says that it was born at the University of Matanzas) but it clearly casts itself as a voice of "revolutionary" Cuban youth and, though sometimes moderate and open to dialogue, seems mostly interested in staunchly defending the revolution and attacking its critics.

A year ago when I launched El Yuma I quickly became acquainted with the emerging Cuban blogosphere.

Three blog portals that I highlighted early on here and here were DesdeCuba, Bloggers Cuba (now defunct), and Havana Times.

DesdeCuba has continued to grow during 2010 in the form of Voces Cubanas and now the three-month-old on-line Revista Voces. Likewise, I have been impressed with the quality and diversity of the reporting over the past year at Havana Times (go here and here to learn more about HT from its editor Circles Robinson - they just celebrated their 2nd anniversary on-line at the end of October).

Now there seems to be a new kid on the "blog": La Joven Cuba.

I'm still unclear on the whole story behind this new blog portal (the site says that it was born at the University of Matanzas) but it clearly casts itself as a voice of "revolutionary" Cuban youth and, though sometimes moderate and open to dialogue, seems mostly interested in staunchly defending the revolution and attacking its critics.

One interesting recent development courtesy of Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo, editor of Revista Voces, is that that digital magazine's new web portal has been made to look exactly like the design of La Joven Cuba. (I assume by using the same standard wordpress theme?)

Anybody care to comment on the resemblence between the two sites? (See the two screenshots, the newer site of Revista Voces at the top and La Joven Cuba here above).

Sunday, November 14, 2010

Pardoned, Not Paroled (Part IV)

Penultimos Dias is reporting that Arnaldo Ramos Lauzurique has been released from prison and is at his home in Cuba. He constitutes the first of the "group of 75" to be released even though he has refused to go into exile. He says he will resume his opposition activities in Cuba.

The Cuban Catholic Church has also announced that the release of all other originally named dissidents will soon follow.

Mauricio Vicent, of El Pais, quotes Ramos as saying, "They told me that my freedom was unconditional... I do not want to leave my country. I will remain and I will continue with the same oppositional activities that I was doing before going to prison."

Vicent also notes, however, that Ramos has been freed under a "special humanitarian license," which is not equivalent to a pardon.

Havana's Archbishop also announced that Luís Enrique Ferrer is also being released today (but will go to exile in Spain along with his family) leaving 11 of the 75 still in prison.

Of the remaining 11, the majority have expressed a desire to stay in Cuba, including Héctor Maseda, condemned to 20 years, and the doctor Oscar Elías Biscet, serving a 25 years sentence. It seems that two of the remaining 11 are disposed to emigrate but directly to the United States.

More info at EFE.

More from Yoani on Party "Guidelines"

"Communist Party Congress To Work on Economy but Not Human Rights"

By Yoani Sánchez

El Comercio, Lima, Peru

November 14, 2010

It is seven in the morning and a crowd is waiting in front of the neighborhood's only newsstand. They aren't there for Granma, an example of a newspaper with few pages and less news, but rather for a booklet with the guidelines of the Sixth Cuban Communist (PCC) Congress to be held next April.

After thirteen years without a meeting of "the highest leading force of society and the State," the next conclave has finally been announced. The last time they met was in 1997, when Fidel Castro — still, today, the Party's first secretary — could improvise long speeches, turning the discussions into one endless monologue.

By Yoani Sánchez

El Comercio, Lima, Peru

November 14, 2010

It is seven in the morning and a crowd is waiting in front of the neighborhood's only newsstand. They aren't there for Granma, an example of a newspaper with few pages and less news, but rather for a booklet with the guidelines of the Sixth Cuban Communist (PCC) Congress to be held next April.

After thirteen years without a meeting of "the highest leading force of society and the State," the next conclave has finally been announced. The last time they met was in 1997, when Fidel Castro — still, today, the Party's first secretary — could improvise long speeches, turning the discussions into one endless monologue.

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

The times they are a changin'

Or is it, "The more things change the more they stay the same"?

Just as I finished reading the 100+ pages of legalese contained in the Gaceta Oficial that makes official Cuba's economic reforms in the area of massive layoffs, self-employment, and the new tax code and social security system for entrepreneurs, the CCP (Cuban Communist Party) comes out with this new 32-page document "Proyecto de Lineamientos de La Political Economica y Social," outlining the aims of its upcoming 6th Party Congress to take place in April, 2011 (H/T to Cafe Fuerte for putting it up so fast!).

Someone at Party headquarters has been busy lately!

Cafe Fuerte has a very useful analysis of the quite significant (economic) changes outlined in the document here in Spanish (Principales puntos del documento del VI Congreso del PCC).

What follows after the break is my own summarized translation of their analysis.

Readers are also encouraged to read La Flaca's always sharp and perceptive analysis here. Sanchez admits that her take on the document is quite skeptical. However, she notes that most potential entrepreneurs do not yet intend to "take the bait" offered by the announced opening in self-employment given the atmosphere of distrust of the government that fills the air.

She also finds it disheartening that not a single line of the document (written by a political party) has to do with the expansion of political or civil rights (like the right to freely leave or return one's own country, not to mention freedom of expression, association, or of the press).

It's all economix.

"The Party will have its Congress in April," Sanchez notes sardonically. "They will approve changes not very different from the ones outlined here and a year or two from now we will be asking ourselves whatever happened with so much spilled ink. Whatever became of that program that aimed to perfect and improve instead of changing and ending?"

Just as I finished reading the 100+ pages of legalese contained in the Gaceta Oficial that makes official Cuba's economic reforms in the area of massive layoffs, self-employment, and the new tax code and social security system for entrepreneurs, the CCP (Cuban Communist Party) comes out with this new 32-page document "Proyecto de Lineamientos de La Political Economica y Social," outlining the aims of its upcoming 6th Party Congress to take place in April, 2011 (H/T to Cafe Fuerte for putting it up so fast!).

Someone at Party headquarters has been busy lately!

Cafe Fuerte has a very useful analysis of the quite significant (economic) changes outlined in the document here in Spanish (Principales puntos del documento del VI Congreso del PCC).

What follows after the break is my own summarized translation of their analysis.

Readers are also encouraged to read La Flaca's always sharp and perceptive analysis here. Sanchez admits that her take on the document is quite skeptical. However, she notes that most potential entrepreneurs do not yet intend to "take the bait" offered by the announced opening in self-employment given the atmosphere of distrust of the government that fills the air.

She also finds it disheartening that not a single line of the document (written by a political party) has to do with the expansion of political or civil rights (like the right to freely leave or return one's own country, not to mention freedom of expression, association, or of the press).

It's all economix.

"The Party will have its Congress in April," Sanchez notes sardonically. "They will approve changes not very different from the ones outlined here and a year or two from now we will be asking ourselves whatever happened with so much spilled ink. Whatever became of that program that aimed to perfect and improve instead of changing and ending?"

Tuesday, November 9, 2010

More on Academic Freedom: Soy de La Florida, pero Viva Nueba Yol!

Defend freedom of travel and academic freedom in Cuba... and in La Florida!

As readers of El Yuma will already know, I'm from the "Panhandle," aka Florida's Redneck Riviera. Me and Joe Scarborough both. (Believe it or not, Morning Joe was my high school football coach!)

I have long advocated for Cubans' right to travel freely within their own country and abroad without the interference of Big Brother. My blogger colleague and friend Yoani Sanchez has been denied this right (along with many other Cubans who refuse to "behave") now something like 8 consecutive times.

On the positive side, both the Cuban and U.S. governments have recently allowed an encouraging surge in academic and artistic travel and exchange, especially with the recent jazz, ballet (and here), and philharmonic visits by American companies to Cuba and with the recent arrival of the critical underground hip-hop acts "Los Aldeanos" and Silvito "El Libre" to Miami for a concert this coming Sunday (ojala que lleguen a Nueba Yol!)

However, it turns out that if you are an academic working at a Florida state school, you cannot use any monies that pass through the hands of Big Brother to travel to or do research in Cuba.

As a (usually) proud American, I believe it is we who should be giving an example of freedom to Cuba, not Cuba who should set the standards of control and limitation for us to imitate. Here is a letter to President Obama from a host of U.S. academic institutions (including my alma mater Tulane University) posted at Cafe Fuerte asking for greater legal authority to carry out academic exchanges with Cuba.

So, though I'm proud to be from Florida, I'm happy to be living in and employed by the State of New York (even with our looming budget crisis).

Feeding Frenzy: Los Aldeanos y Silvito "El Libre" arrive in Miami

Cuban underground hip-hop artists "Los Aldeanos" and Silvito "El Libre" (son of Silvio Rodriguez) arrive in Miami for a joint performance later this week.

Penultimos Dias has a link to an article on the musicians at Miami New Times, Cafe Fuerte has put up a long, detailed TV interview here, and there's a cringe-worthy video from Telemundo below after the break.

Watch the video for yourself (it's under 5 minutes long), but I find the media "feeding frenzy" in the airport upon the arrival of these valiant artists to be a bit sad and embarassing. The Telemundo reporters try again and again to provoke them into saying something "political" but they keep their composure and talk only of peace and unity among Cubans.

They even ask Silvito how he feels about being the son of Silvio Sr. and he replies simply, "proud." How many of us are both proud to be our parents children while disagreeing with them over politics and generational committments?

If you want political or provocative listen to their music and watch their videos here, here, here, and here.

Monday, November 8, 2010

It's Party Time, Cuban Style

Cafe Fuerte is reporting that the Cuban government has announced that it will hold the 6th Congress of the Communist Party in the second half of April, 2011. (See also Granma).

The main goal of the Congress, announced by President Raul Castro on Monday, November 8, 2010, at a meeting with Hugo Chavez commemorating 10 years of cooperation between Cuban and Venezuela, is to analyze "the updating of the economic and social model of the country."

The 5th Party Congress took place in 1997 and the 6th was set to take place eight years later in 2002. However, it has been repeatedly postponed.

Castro also announced the start of a national popular debate over "the social and political aims of the country" set to take place from December 1, 2010 through February 28, 2011. The debate is to be based on a guiding document that will appear tomorrow, sold for one peso in all the nation's newsstands.

Keep reading to hear Granma tell it... (in other words, "It's the economy, stupid").

The main goal of the Congress, announced by President Raul Castro on Monday, November 8, 2010, at a meeting with Hugo Chavez commemorating 10 years of cooperation between Cuban and Venezuela, is to analyze "the updating of the economic and social model of the country."

The 5th Party Congress took place in 1997 and the 6th was set to take place eight years later in 2002. However, it has been repeatedly postponed.

Castro also announced the start of a national popular debate over "the social and political aims of the country" set to take place from December 1, 2010 through February 28, 2011. The debate is to be based on a guiding document that will appear tomorrow, sold for one peso in all the nation's newsstands.

Keep reading to hear Granma tell it... (in other words, "It's the economy, stupid").

Pardoned, Not Paroled (Part III)

From a communique posted at #OZT - I Accuse the Cuban Government (H/T Penultimos Dias):

“We have arrived at the end of the time frame and the only clear conclusion is the following: there have been massive deportations of dissidents and their families overseas, but there have been no effective liberations in Cuba. The Black Spring political prisoners remain in jail, even though thier names were on the initial lists.

Paradoxically, the political prisoners who remain in jail are the very ones who have refused to leave the country. We say, ‘paradoxically,’ because it is just these releases that should be the easiest to carry out given that granting their freedom requires no cumbersome bureaucratic wrangling so that they can reside abroad. The message is clear: there is space neither for the opposition nor for freedom in Cuba.”

Sunday, November 7, 2010

Vamos a Cuba? El arte de la espera...

For those (like me) who have been frustrated by the Obama administration's lack of "audacity" in changing Cuba policy, it is good to remember what HAS changed.

Cuban-Americans can now travel and send money to their relatives back home at will (a very positive change in humanitarian terms) and visas for Cuban artists and academics have been regularly granted (good for the free flow of culture, information, and ideas).

In fact, tonight I'm having dinner here in NYC with an old friend I got to know in Havana in the late 90s, the Cuban artist Sandra Ramos. She's currently on an art and lecture tour in the U.S. and gave a well-attended talk on contemporary Cuban art at CUNY's Bildner Center on Friday.

(I'd summarize the attitude of most of the art/artists she featured as a sharp mix of "burla," "critico," y "cinico" vis-a-vis current Cuban reality. One person in the audience even surprised her by asking if there weren't any "revolutionary" artists working in Cuba today!)

This past year here in New York we've benefitted from an embarrassment of riches in terms of visiting artists and intellectuals. I've seen La Charanga Habanera, Carlos Varela, Pupi, and even "la voz da la nostalgia izquierdista" Silvio Rodriguez. I also caught a lecture here by leading reform-minded Cuban economists Omar Everleny Perez Villanueva and Armando Nova back in the spring.

Cuban-Americans can now travel and send money to their relatives back home at will (a very positive change in humanitarian terms) and visas for Cuban artists and academics have been regularly granted (good for the free flow of culture, information, and ideas).

In fact, tonight I'm having dinner here in NYC with an old friend I got to know in Havana in the late 90s, the Cuban artist Sandra Ramos. She's currently on an art and lecture tour in the U.S. and gave a well-attended talk on contemporary Cuban art at CUNY's Bildner Center on Friday.

Y cuando todos se han ido, llega la soledad. Calcografía. 60x50cm

(I'd summarize the attitude of most of the art/artists she featured as a sharp mix of "burla," "critico," y "cinico" vis-a-vis current Cuban reality. One person in the audience even surprised her by asking if there weren't any "revolutionary" artists working in Cuba today!)

This past year here in New York we've benefitted from an embarrassment of riches in terms of visiting artists and intellectuals. I've seen La Charanga Habanera, Carlos Varela, Pupi, and even "la voz da la nostalgia izquierdista" Silvio Rodriguez. I also caught a lecture here by leading reform-minded Cuban economists Omar Everleny Perez Villanueva and Armando Nova back in the spring.

Pardoned, Not Paroled (Part II)

Today, Sunday, November 7, 2010, is the ostensible deadline for the release of the final 13 Cuban political prisoners of the remaining 52 of the original "75" from 2003.

Renato Pérez Pizarro at Miami Herald's Cuban Colada Blog indicates that Cuba has been releasing other prisoners not on the list, some of whom are relatively or totally unknown to human rights groups.

Some suspect this is a strategy (a la Mariel) to taint the political prisoners by mixing their release (and deportation) with that of common criminals and with prisoners who have indeed used violence in the past.

Still, the most important question remains whether the Cuban government will release and "pardon, not parole" the remaining prisoners who refuse the be banished from their homeland.

Vamos a ver!

A few reminders from last week's post:

Renato Pérez Pizarro at Miami Herald's Cuban Colada Blog indicates that Cuba has been releasing other prisoners not on the list, some of whom are relatively or totally unknown to human rights groups.

Some suspect this is a strategy (a la Mariel) to taint the political prisoners by mixing their release (and deportation) with that of common criminals and with prisoners who have indeed used violence in the past.

Still, the most important question remains whether the Cuban government will release and "pardon, not parole" the remaining prisoners who refuse the be banished from their homeland.

Vamos a ver!

A few reminders from last week's post:

Saturday, November 6, 2010

Not Your Father's Exile? Values vs. Policy (Part II)

A young Cuban-Amerian friend from Miami whom I met while we campaigned together for Obama back in 2008 (and who now works for the administration) shared the following comment with me regarding Rubio's recent election and Lopez-Levy's article in Foreign Policy.

This friend is about the same age as Rubio and, though very different from him politically, can understand as an insider some of the more nuanced and apparently contradictory political dynamics of the Cuban-American community.

This friend is about the same age as Rubio and, though very different from him politically, can understand as an insider some of the more nuanced and apparently contradictory political dynamics of the Cuban-American community.

I think the polls, while hitting on an inevitable shift in exile thinking as the older generation fades away, miss an essential point about the current Cuban-American electorate.

As in so much in politics, their vote preferences are about values, not policy. Cubans here do increasingly support lifting parts of the embargo.

But even many of them would prefer to see their politicians taking a tough and principled - if blunt and ineffective - stance against the regime rather than siding with the agricultural interests and Castro sympathizers they see pushing for policy changes.

It's part of the messaging problem for advocates.

Digital Disruption II: More from Foreign Affairs

Here are a few more key passages from the Foreign Affairs article, "Digital Disruption," by Google's Schmidt and Cohen:

Digital Disruption: Mobile Technology and Civil Society according to Google's Schmidt and Cohen

This just in from one of my stellar students.

"The Digital Disruption: Connectivity and the Diffusion of Power"

By Eric Schmidt and Jared Cohen

Foreign Affairs, November/December 2010

A video of the presentation is available here and audio here.

Summary:

Increased connectivity allows for the spread of liberal, open values but also poses a number of dangers. To foster the free flow of information and challenge authoritarian regimes, democratic states will have to learn to create alliances with people and companies at the forefront of the information revolution.

Opening section:

The advent and power of connection technologies -- tools that connect people to vast amounts of information and to one another -- will make the twenty-first century all about surprises. Governments will be caught off-guard when large numbers of their citizens, armed with virtually nothing but cell phones, take part in mini-rebellions that challenge their authority. For the media, reporting will increasingly become a collaborative enterprise between traditional news organizations and the quickly growing number of citizen journalists. And technology companies will find themselves outsmarted by their competition and surprised by consumers who have little loyalty and no patience.

"The Digital Disruption: Connectivity and the Diffusion of Power"

By Eric Schmidt and Jared Cohen

Foreign Affairs, November/December 2010

A video of the presentation is available here and audio here.

Summary:

Increased connectivity allows for the spread of liberal, open values but also poses a number of dangers. To foster the free flow of information and challenge authoritarian regimes, democratic states will have to learn to create alliances with people and companies at the forefront of the information revolution.

Opening section:

The advent and power of connection technologies -- tools that connect people to vast amounts of information and to one another -- will make the twenty-first century all about surprises. Governments will be caught off-guard when large numbers of their citizens, armed with virtually nothing but cell phones, take part in mini-rebellions that challenge their authority. For the media, reporting will increasingly become a collaborative enterprise between traditional news organizations and the quickly growing number of citizen journalists. And technology companies will find themselves outsmarted by their competition and surprised by consumers who have little loyalty and no patience.

Friday, November 5, 2010

It Ain't Your Father's Cuba (but is it still his exile?)

My friend and colleague Arturo Lopez-Levy just sent me the following link to his new commentary in Foreign Policy magazine written in reaction to the election of Marco Rubio to the US Senate and Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen's move to become head of the Committee on Foreign Relations now that the Republicans control Congress.

I've heard Arturo's argument before and he makes it well.

The problem is that we keep waiting for this "new generation" of Cuban migrants to make their voices heard by breaking with the old school hardliners and electing someone with a more pragmatic, pro-engagement approach to Cuba.

But it hasn't happened.

What's so special about Cuba(ns)?

WNYC's public radio/NPR station has a new website and blog - "It's a Free Country."

Rodolflo de la Garza, a migration scholar at Columbia who blogs regularly there, put up a provicative post recently, "What's so special about Cuba?" suggesting that the special treatment of Cubans as refugees should end.

"As a matter of principle," he writes, "and given our self-image as a nation committed to fair play, we should immediately end the favoritism with which we treat Cuban unauthorized immigrants."

His main argument supporting this position is that the Cold War ended in 1991 and Cubans' special treatment as "automatic refugees" should have ended with it. But anyone familiar with U.S.-Cuban relations knows that while the Cold War may have ended with the collapse of the USSR, no one seems to have told Washington and Havana that the war is over.

So, should Cubans continue to be aforded special treatment and political asylum as refugees, or should they be treated like any other immigrants? Readers of El Yuma can weigh in here or go to the comments section of Rudy's post above where a lively discussion is already underway.

My two cents: Refugee and asylum status should be granted on the basis of an individual's well-founded fear of persecution. Thus, some Cubans can rightfully claim persecution and should be granted refugee status in the U.S. But refugee status should not be granted to the nationals of any nation en masse. Such a policy sets up a double standard and cheapens the value of the refugee distinction. Also, imagínate, what if we granted that same special treatment to todos los chinos, hasta el yuma estaria hablando en chino dentro de poco!

Buena Vista Social Blog - A la venta!

A new book has just been published in Spain (in Spanish) about the emerging Cuban blogosphere. It is entitled, Buena Vista Social blog: The Internet and Freedom of Expression in Cuba.

Here is a link to the table of contents.

El Yuma even has his own essay among the 25 entries that make up the book. It is entitled, "En busca de la 'Generación Y': Yoani Sánchez, la blogósfera emergente y el periodismo ciudadano de la Cuba de hoy," pp. 201-242 [In Search of Generation Y: Yoani Sánchez, the emergent Cuban blogosphere, and citizen journalism in Today's Cuba].

Keep reading below for more infomation on the book and its 25 contribuitors.

Plane With 68 Aboard Crashes in Cuba

AP: November 05, 2010

HAVANA (AP) - A passenger plane flying from the eastern city of Santiago de Cuba to Havana crashed with 68 people aboard, Cuba's state television reported on Thursday night.

There was no immediate word on whether any passengers survived the crash.

State television said the AeroCaribbean flight went down near the village of Guasimal, in Sancti Spíritus Province. It was carrying 61 passengers and a crew of seven. The report said that 28 of the passengers were foreigners, but it did not provide a breakdown of their nationalities.

In Havana, relatives of those on board the plane were kept away from other passengers.

The newscast gave no details on what happened, saying only that the cause of the crash was being investigated.

The flight was one of the last to leave Santiago de Cuba for Havana ahead of Tropical Storm Tomas, which was on a track to pass between Cuba and Haiti.

Sent via BlackBerry from T-Mobile

HAVANA (AP) - A passenger plane flying from the eastern city of Santiago de Cuba to Havana crashed with 68 people aboard, Cuba's state television reported on Thursday night.

There was no immediate word on whether any passengers survived the crash.

State television said the AeroCaribbean flight went down near the village of Guasimal, in Sancti Spíritus Province. It was carrying 61 passengers and a crew of seven. The report said that 28 of the passengers were foreigners, but it did not provide a breakdown of their nationalities.

In Havana, relatives of those on board the plane were kept away from other passengers.

The newscast gave no details on what happened, saying only that the cause of the crash was being investigated.

The flight was one of the last to leave Santiago de Cuba for Havana ahead of Tropical Storm Tomas, which was on a track to pass between Cuba and Haiti.

Sent via BlackBerry from T-Mobile

Thursday, November 4, 2010

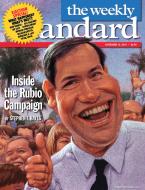

Marco Rubio: The GOP's "Great Right Hope"?

From today's Times (link below):

“He’s our Cuban Barack Obama,”

said Alex Lacayo, 36, a campaign volunteer for

Senator-elect Marco Rubio.

“He gives us hope.”

Ernesto at Penultimos Dias has posted this series of interesting links to reactions and analysis on the election of Cuban-American (hijo orgulloso de exiliados cubanos) Marco Rubio. The plot thickens...

Notimex: El senador electo Marco Rubio dice que fortalecerá línea dura contra Cuba.

PD: Rui Ferreira, en El Mundo, sobre Rubio.

PD2: La interpretación de Rubio de las relaciones Cuba-EE UU puede verse en esta intervención (video), del año pasado.

PD3: Damien Cave en The New York Times, sobre “la gran esperanza conservadora”.

Wednesday, November 3, 2010

Senator-Elect Marco Rubio - "Simply the greatest nation in all of human history"

I was born and raised in Pensacola, Florida. So, who that state's elected officials are interests me. Of course, we all know of Florida's inordinate importance in Presidential electoral politics (remember good ole 2000?). Moreover, Florida has long been the tail that wags the dog of U.S. Cuba policy.

I am also a life-long Democrat, a consistent critic of the Cuban regime who nonetheless favors "principled engagement" with it, and a skeptic who, I'll admit it, rolls his eyes and cringes when he hears the following words:

"Americans believe with all their heart -- the vast majority of them, and the vast majority of Floridians -- that the United States of America is simply the greatest nation in all of human history. A place without equal in the history of all mankind."

So, it goes without saying that if I still lived in Florida, I would NOT have voted for its new senator elect, Marco Rubio (Herald story here and Human Events here). Still, whatever you think about this young, rising star of the tea party movement and Republican Party, El Yuma advises you to do three things now:

Tuesday, November 2, 2010

News Roundup: Taxes, Agriculture, and the Economic and Political Outlook

Here are links to a number of enlightening articles (all from the good people at Reuters) dealing with the fits and starts of Cuban reform in agriculture, the tax system, and self-employment. The last article also contains a bit about U.S.-Cuban relations.

- Reuters' Nelson Acosta on last Monday's release of the new tax code for the self-employed.

- Reuters' Marc Frank on the worries of Cuban farmers over the pace of reform. Two steps forward and one step back. As usual, the English version of the article is shorter and less enlightening than the Spanish version. Still, in both versions Cuban economist Armando Nova is quoted as saying, "The contracting system should be reduced to the indispensable so that most production can be sold on the basis of supply and demand." The Spanish version of the article also includes this provocative critique of Cuba's state food production and distribution system from Cuban economist Juan Triana: "No se puede seguir viviendo presos de cabezas acomodadas que no alcanzan nunca a ver la solución que está al alcance de sus narices" (or to paraphrase: "We can't keep being prisoners of comfortable leaders who never manage to see the solutions that are right under their noses" - thanx to a reader for help on that translation). Also see these older articles and blog posts for useful background on economic debates about the role of Cuba's private sector. Go here from March on agriculture, go here from April on a lecture in New York by Cuban economists Armando Nova and Omar Perez Villanueva, and go here from August on Marc Frank's soundings of Cuban farmers.

- Finally, Reuters' Jeff Franks has this sharp analysis of the key political risks to watch for in Cuba in the months to come (H/T Penultimos Dias).

Pardoned, Not Paroled (Part I)

Renato Pérez Pizarro at Miami Herald's Cuban Colada Blog summarizes an interesting AP article by Paul Haven on the looming November 7 deadline for the final 13 of the promised 52 Cuban prisoner releases.

These final 13, however, refuse to be deported upon release. Pérez Pizarro, says, "They refuse to leave prison unless they are freed without any conditions – pardoned, not paroled."

The article also says that hunger striker and recent winner of Europe's Sakharov human rights prize Guillermo Farinas will stop eating again on Nov. 8 if the remaining dissidents are not in their homes by that date.

Leading dissident Elizardo Sanchez argued that Cuba's leaders have nothing to gain - and everything to lose - by keeping the last 13 prisoners in jail. "By releasing them, the government improves its international image and removes a weight off its back. If it does not, it will gain only the world's condemnation," Sanchez said. "Not freeing them would be unthinkable."

These final 13, however, refuse to be deported upon release. Pérez Pizarro, says, "They refuse to leave prison unless they are freed without any conditions – pardoned, not paroled."

The article also says that hunger striker and recent winner of Europe's Sakharov human rights prize Guillermo Farinas will stop eating again on Nov. 8 if the remaining dissidents are not in their homes by that date.

Leading dissident Elizardo Sanchez argued that Cuba's leaders have nothing to gain - and everything to lose - by keeping the last 13 prisoners in jail. "By releasing them, the government improves its international image and removes a weight off its back. If it does not, it will gain only the world's condemnation," Sanchez said. "Not freeing them would be unthinkable."

Friday, October 29, 2010

¡PROTESTO! - Omni Zona Franca - ¡La Famila en Movimiento! - ¡Empingao asere¡

Omni Zona Franca en Alamar (1995-2010)

Click below to watch this hip-hop music video don't forget to turn it up! Direct from Habana del Este.

Title: ¡PROTESTO! - ¡La Famila en Movimiento!

Thursday, October 28, 2010

Happy Birthday to Me! - Blog stats for the curious

El Yuma (aka, Theodore Aloysius Henken II, aka, Ted) turned 39 on October 7, 2010.

Today this blog, also called El Yuma, turns one year old. We've been on-line for a year. Hooray!

It turns out that back on October 7 the readers of the blog gave me an inadvertant birthday gift. On that day, the blog received a new record of 217 visits in a single day, most coming to see the post "Twitter responds and we learn a few lessons" (many visitors were referred by Ernesto over at Penultimos Dias - thanx Ernesto).

I want to give a big, fat, Cuban "mil gracias" to all my loyal readers, commentators, those who have sent me individual e-mails, and especially to those who have placed El Yuma on thier blogrolls and linked to me in their posts over the past year.

Referral sources are one of the main way a blog grows, gains followers, and establishes a profile in the web. The leading referral sources over the past year for El Yuma are: Yoani and her gang over at DesdeCuba.com (5,705), Phil at The Cuban Triangle (4,050), Tracey at Along the Malecon (1,494), Ernesto at Penultimos Dias (1,249), and Wilfredo and Ivette at Cafe Fuerte.

For those interested, what follows is a round-up of the stats from the past year, from my very first blog post on October 29, 2009, "Aplatanado" through the Taxman post I put up yesterday, October 27.

Wednesday, October 27, 2010

The Taxman Comes to Cuba (Part I)

El Yuma has a new post up at The Havana Note on Cuba's new tax regime for self-employment. After I work my way through the new regs from La Gaceta Oficial, I will post a follow up. Stay tuned.

PS: Can anyone guess the name of another Beatles song that coincides with the significance of tomorrow, Thursday, October 28, for readers of El Yuma? Hint, the Brazilians say, "Para Bens!" on this day.

That's right - El Yuma cumple un año de existencia mañana!

Monday, October 25, 2010

Aqui Estan - PDFs of La Gaceta Oficial Nos. 11 & 12

For those interested in the fine print, here are the full texts of the two new groups of "decree-laws" regarding the layoffs, self-emplyment, and taxes for the self-employed released to the public in Havana this morning.

First, there is the relatively short 17-page group of seven laws grouped together in La Gaceta Oficial No. 11 (officially dated October 1, 2010). Then there is La Gaceta Oficial No. 12 (dated October 8).

Courage! This second document is 81 pages long with 14 different resolutions or decree laws. Everything from layoffs to the new tax regime for the self-employed.

Some smoke clears on Cuban taxes, but there's a long road ahead

Here are links to five sites with info on the detailed new tax procedure and self-employment regulations made official this morning when they were published in Cuba's Gaceta Oficial.

Friends in Cuba tell me that there are long lines both at the self-employment offices and at the various newsstands that sell the two special issues of La Gaceta (Nos. 11 and 12).

I went to La Gaceta's website (and here) to see if I could download the regs. They are there but given Cuba's slow internet speeds (and perhaps the high demand for these particular regs), it takes a while to download them. Once you have them, however, I hope you have better luck than I at opening/viewing them as they are in the Russian compression program .rar.

Go here for Paul Haven's AP story.

Go here for a brief summary at the Cuba Standard Blog.

Here is Prensa Latina's take (H/T Penultimos Dias).

Finally, Granma gives the following brief announcement here. It will cost you 1.40 in Cuban pesos.

Friends in Cuba tell me that there are long lines both at the self-employment offices and at the various newsstands that sell the two special issues of La Gaceta (Nos. 11 and 12).

I went to La Gaceta's website (and here) to see if I could download the regs. They are there but given Cuba's slow internet speeds (and perhaps the high demand for these particular regs), it takes a while to download them. Once you have them, however, I hope you have better luck than I at opening/viewing them as they are in the Russian compression program .rar.

Go here for Paul Haven's AP story.

Go here for a brief summary at the Cuba Standard Blog.

Here is Prensa Latina's take (H/T Penultimos Dias).

Finally, Granma gives the following brief announcement here. It will cost you 1.40 in Cuban pesos.

Centro de distribución en La Habana de la Gaceta Oficial, que ayer publicó el paquete legal de reformas que, entre otras disposiciones, marca el final de casi cinco décadas en las que el Estado cubano garantizó a todos los trabajadores una plaza o un seguro de desempleo que podía ser indefinido. Foto Reuters.

"A la venta Gaceta Oficial extraordinaria especial 11 y 12"

Desde hoy lunes comienza la venta en todas las oficinas de correos y estanquillos de prensa del país, de la Gaceta Oficial, de carácter extraordinaria especial, números 11 y 12.

El contenido de la Gaceta Oficial número 11 recoge las Disposiciones Generales dictadas por los Consejos de Estado, de Ministros y su Comité Ejecutivo, acerca del proceso de reducción de las plantillas infladas, y la ampliación del ejercicio del trabajo por cuenta propia.

La edición número 12 contiene las normas que complementan dichas Disposiciones Generales, por medio de resoluciones emitidas por los ministerios de Trabajo y Seguridad Social, Finanzas y Precios, Transporte, Agricultura; del Banco Central de Cuba y el Instituto Nacional de la Vivienda.

La Gaceta Oficial número 11 tiene un precio de cuarenta centavos, y la 12 de un peso.

Sunday, October 24, 2010

A Different Take on Cuba's New Tax Laws

On Friday, El Yuma posted Granma's article detailing Cuba's new tax system for the self-employed along with a link to an AP article by Paul Haven describing that system.

This Reuters article by Marc Frank also unpacks the Granma article, but has a substantially different take on the significance of new tax regime and its difference from the "rudimentary" one put in place back in 1994.

Phil Peters also put up a helpful summary on Friday on his blog, The Cuban Triangle.

I will post my own analysis here on Monday - so stay tuned.

Friday, October 22, 2010 - By Marc Frank

HAVANA (Reuters) - Cuba unveiled on Friday a new tax code it said was friendlier for small business, signaling authorities are serious about building a larger private sector within the state-dominated economy.

The new system, outlined in the Communist Party daily Granma, greatly increases tax deductions, but also adds taxes and comes with a warning of stiffer enforcement of tax collection.

It replaces a rudimentary tax code in place since 1994 when some self-employment was first authorized but then squeezed by severe regulation.

This Reuters article by Marc Frank also unpacks the Granma article, but has a substantially different take on the significance of new tax regime and its difference from the "rudimentary" one put in place back in 1994.

Phil Peters also put up a helpful summary on Friday on his blog, The Cuban Triangle.

I will post my own analysis here on Monday - so stay tuned.

A portrait of former Cuban leader Fidel Castro is seen on the wall as a watchmaker works at his stall in Havana October 22, 2010. Credit: Reuters/Enrique De La Osa

Friday, October 22, 2010 - By Marc Frank

HAVANA (Reuters) - Cuba unveiled on Friday a new tax code it said was friendlier for small business, signaling authorities are serious about building a larger private sector within the state-dominated economy.

The new system, outlined in the Communist Party daily Granma, greatly increases tax deductions, but also adds taxes and comes with a warning of stiffer enforcement of tax collection.

It replaces a rudimentary tax code in place since 1994 when some self-employment was first authorized but then squeezed by severe regulation.

Friday, October 22, 2010

Adios a la libreta?

Nick Miroff of NPR has a great audio story from this morning's Morning Edition on the fate of Cuba's much maligned and much needed ration booklet. The story, "Amid Reforms, Cubans Fret Over Food Rations Fate," can be heard (and read) at NPR. A translation of the story is up at Penultimos Dias.

Also, go here for a related story in this month's Harper's Magazine by American journalist Patrick Symmes, "Thirty Days as a Cuban," on his attempt to live on the average Cuban wage for one month. My colleague, the anthropologist Ariana Harnandez Reguant, sent me the provocative article which seems to have caused a bit of a debate among Cuba-watchers.

Finally, I'm pasting below my own somewhat-lengthy description of the history of the ration booklet in Cuba taken from my book.

The Ration Booklet—A Cuban Staple

By 1962, the Cuban government had nationalized all major industries and was thus responsible for producing goods and services in sufficient quantity and at prices manageable for the mass of citizens who had supported the revolution.The Taxman Arriveth to Cuba - "Más valen las cuentas claras" - desde Granma

You won't often find El Yuma reproducing an entire article from Granma, but this morning's paper has an extensive article covering the details of the new tax system to be put in place for the self-employed.

I will review this over the weekend and give my own analysis and interpretation next Monday.

Go here for a preliminary report from the Havana AP bureau chief Paul Haven (H/T from the always sharp Cuban Colada blog).

En materia de tributos

Más valen las cuentas claras

El pago de tributos en Cuba no es nuevo, pero en el actual escenario económico también se rediseña la política tributaria

LETICIA MARTÍNEZ HERNÁNDEZ y YAIMA PUIG MENESES

La Habana, 22 de octubre de 2010 - Casi todos hemos pagado tributos alguna vez en la vida. Sin embargo, no siempre sabemos cómo los abonamos, cuál es su destino o mediante qué mecanismos se recaudan. Y es que, aun cuando a diario rehacemos números y cuentas para equilibrar los gastos hogareños, poco conocemos sobre conceptos como impuestos, tasas o contribuciones.

Todos los tributos se pagarán en moneda nacional independientemente del tipo de moneda en que operen los trabajadores por cuenta propia.

An Oldie but a Goodie - Who's Bitter?

A relic of crumbling Soviet era architecture along the Malecon, Havana's waterfront boulevard and seawall

Exclusive to Huffington Post

Rarely does a person interviewed complain that a journalist has interpreted their statements to the letter; more frequently the opposite occurs, when, whether from negligence or malicious intent, a clear statement is ignored, mutilated or misinterpreted. So even though Fidel Castro has accustomed us to think of him as different from common mortals, we were surprised when he said he meant the exact opposite of what he said when he told Jeffrey Goldberg from The Atlantic magazine that, "The Cuban model doesn't even work for us anymore."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)